Eliza Thompson was very excited. She was about to marry her childhood sweetheart, Charles Conn. The date was November 24, 1857 and the happy event was to be held in the Ballee Church of Ireland, not far from their parents farms at Ballyclander Lower.

The Conn and Thompson families had been preparing for weeks beforehand, and the whole community was involved in the detailed preparations. They were a close community and a wedding was always an opportunity for people to come together to celebrate.

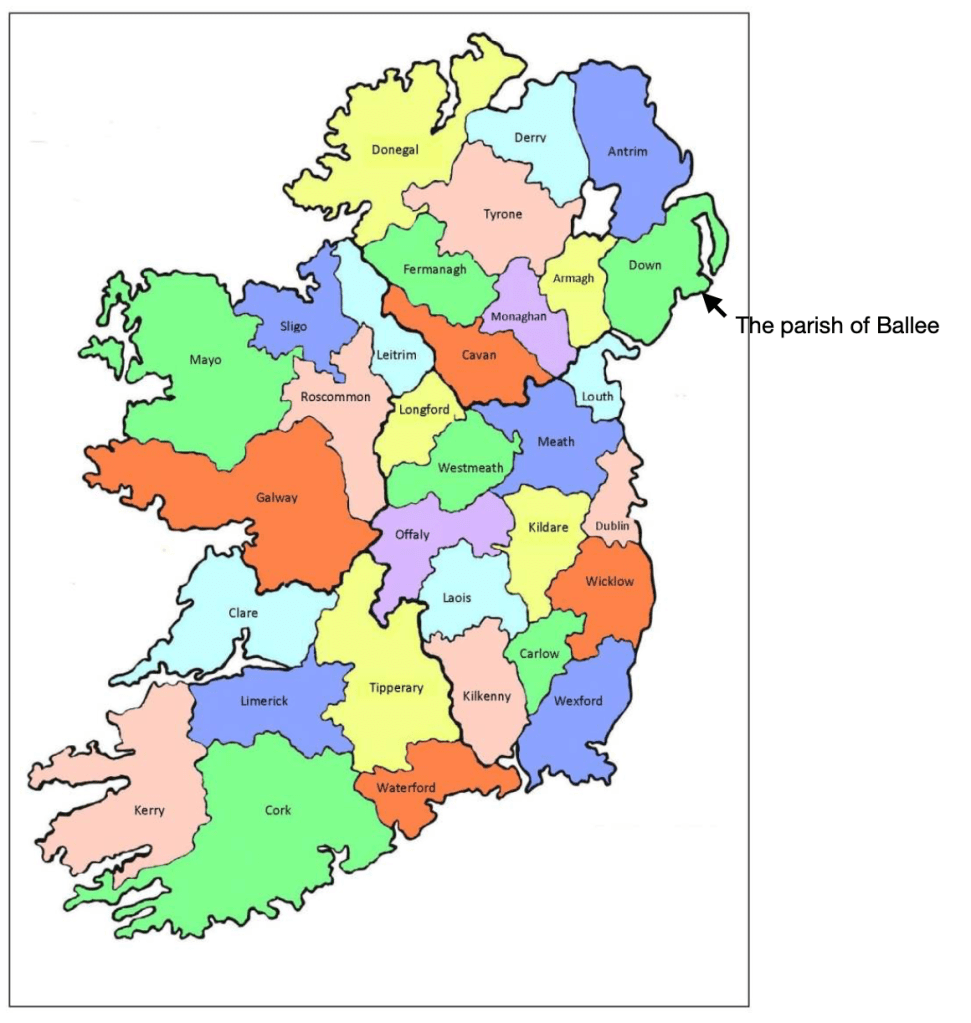

The parish of Ballee was located in the Barony of Lecale, on a peninsula on the south east coast of Northern Ireland, tucked in between the Mountains of Mourne and Strangford Lough. Ballcylander Upper and Lower were Townlands situated on the road between Downpatrick and Ardglass – about five miles south of Downpatrick and four miles, or an hour’s ride by horse and cart to Ardglass.

Ardglass had been a fishing port for 2000 years and was an important town and port in the Middle Ages, though it wasn’t until after 1812 that a harbour was constructed. The picturesque fishing village and seaside resort on the Irish Sea was in its heyday as a fishing port at the time of Eliza and Charles’ wedding. The harbour master at that time was Captain Bernard Hughes who invented and patented the keystone method of constructing sea walls in 1849-51 which involved stones being set together without the use of mortar to allow them to expand when being pounded by wave action.

Despite its economic importance the smuggling of contraband such as tobacco, rum and brandy occurred along the coast of Lecale. The cargo would be brought in from the Isle of Man at night and concealed in caves along the coast near Ardglass. It was later transferred by road to merchants around Ireland. Smuggling had occurred in this area for decades and during their childhood Charles and his brothers delighted in stories and games about smugglers.

A walk of an hour or so west of Ardglass was the harbourside village of Killough. Charles’s grandparents, James and Ann Conn lived in Killough and on visits to them it was always exciting to visit the harbour and look south along the coast to where the Mountains of Mourne swept down to the sea. It would be another 30 years before Irish musician, Percy French wrote the song that would make those picturesque mountains famous worldwide. Charles’ mother Ann Hawthorn was born in Killough, on April 16, 1811. Her father William was born there in 1782 and died there in 1875. His wife, Anne Jane Brown was born in 1790 and died in 1840. In 1845 he married again to Catherine Caine at Coney Island, a tiny hamlet between Killough and Ardglass.

While Downpatrick was a little further away it was the biggest town in the area and it was always a big event, on special occasions, to put on their best clothes, load the horse and cart, and head off to Downpatrick for a day’s outing. For the men, it was usually about buying tools and products to assist with farming or to make contact with farming agents who were prepared to buy their barley. The women enjoyed looking in the shop windows and wondering about the latest fashions that had come from Belfast and Dublin, and occasionally from London.

Downpatrick had a unique history and strangers would often be seen in town, visiting what was believed to be the grave of St Patrick, after whom the town was named. St Patricks remains were said to have been buried in the grounds of the imposing Down Cathedral that towered over Downpatrick from Cathedral Hill.

Charles would roll his eyes as a boy every time the family went into Downpatrick and his father would tell about coming to Downpatrick as a boy, and watching the stone masons at work building the perpendicular Gothic tower that was added to the newly built cathedral. This new cathedral was built on the site of the ruins of a 14th century cathedral, which in itself had been built on an ancient ecclesiastical site from the 12th century.

Charles was born in Ballyclander on August 10, 1833. He was now 24 years old and knew nothing of the world apart from his life on the farm. He most likely attended school at Church Ballee, the closest school to Ballyclander. He loved the green rolling hills of his home town and when he left school quickly became involved in the various activities of their barley farm. Both Charles parents John and Ann Conn had grown up in the area. John was born here in 1815 and would die here only eight years later. His mother Ann would survive for another 43 years, dying at the ripe old age of 89 in Ballybranagh, just beyond the Mournes.

Eliza was 20, born in 1837. Her father John Thompson was born in Ballywillen in 1805 and her mother Agnes Lascelles was born in 1806. Both lived their lives in or near Ballyclander and would end their lives there, John in 1886 and Agnes in 1879.

Charles and Ann grew up on nearby farms. According to the Griffiths valuation they lived two farms from each other, both owned by William Johnston, possibly the same Johnston who was to become a politician. In 1867, Johnston organised an Orange Order parade from Bangor to Newtownards in County Down despite the Party Procession Acts. The parade took part on 12 July 1867 and about 30,000 took part. Johnston was sentenced to a short term in prison the next year for his actions. He was elected as Member of Parliament for Belfast in 1868 and held the seat until 1878. He was called to the Bar at King’s Inns Dublin in 1872. Johnston was also a prominent early supporter of the campaign for female suffrage and other social reforms. But that was still in the future.

At the time of the wedding two of the neighbouring properties in Ballyclander Lower were part of the Magharafelt Charity Estate. The Griffiths valuation show that both Thomas and James Newell were tenants of properties in this estate, though Thomas Newell was a landlord of three houses in his own right. There were less than a dozen families living in Ballyclander Lower at the time, according to the Griffith Valuation.

Hugh Rainey, an iron smelter and wealthy merchant in the Magherafelt district in the north of Ireland, devoted one half of his estate in 1707 to fund a charity school for 24 boys, “sons of parents who were of good report and reduced to poverty”. The Rainey Endowed School in Magherafelt remains to this day. Following Rainey’s death the trustees purchased an estate that became known as the Ten Towns of Lecale. Ballyclander Upper and Lower were among these 10 towns that formed the estate. Half of the rent of these properties was to go to the Magharafelt School. Over time many of the tenants of the estate were given the opportunity to purchase for Mr Rainey an annuity of 50 pounds, thus providing security of tenure.

There were hundreds of flax growers in County Down, and a number scattered through the Ballee parish, but according to the 1796 list of flax growers in Ireland, there were none in Ballyclander. The 1796 list consisted of about 60,000 growers who were given incentives for growing flax. The Irish Linen Board decided on a scheme of incentives to get people to grow the crop. Individuals were rewarded with 4 spinning wheels for planting one acre of flax. As a result by the end of the 19th century, Belfast was the linen capital of the world. Perhaps the families of Ballyclander chose to stay with traditional crops rather than investing in the popular alternative.

Today, hats were being doffed and children excitedly ran around the grounds of the parish church as people began to gather in preparation for the wedding. Charles, the eldest of the Conn children, was the first of his family to get married. Edward was just two years younger, then came William, a strapping young 19-year-old, followed by his two teenage sisters, Ann (15) and Catherine (13). James was only 11 years old at the time and his baby sister Bessy was just nine.

Eliza only had a brother and sister, Jane who was 18 and John, aged 16.

Catching up with cousins, uncles and aunts, and other family friends and relatives was an important part of a wedding such as this.

There were the Perry’s from Ballyhosset. John Perry was one of Charles and Eliza’s witnesses as well as Sarah Jane West. The West family lived on an adjoining farm to the Conns in Lower Ballyclander. Mary West was listed in the Griffith valuation as the tenant of a farming property whose landlord was James McDowell. Eliza’s mother’s family, the Lascelles lived in the nearby townland of Church Ballee. Charles’ aunt, his mother’s sister Margaret, was married to a Lascelles, so many of both Charles and Eliza’s cousins bore that surname, and were no doubt at the wedding in force.

The Ballee Church was described as a plain building without a spire or aisle but was capable of seating 220 people. A graveyard was attached to the church, with the dates on gravestones going back to 1679. There had been a church on that site, though not the same building, since 1306. The existing building was constructed in 1749 on the site of the old church. The gravestones, if they had been able to speak, would have many tales to tell.

But even before that first gravestone was laid the stones around Ballee would have had their own stories to tell.

In 1175 after a period of fighting between the Normans and Irish, the Irish High King, Rory O’Connor sued for peace with King Henry II of England who agreed to a status quo allowing the Normans to consolidate their conquests in return for no more incursions into Gaelic territory. Henry’s Norman vassals however remained restless. In 1176, John de Courcy came to Ireland and around the start of 1177, went about carefully planning an invasion of Ulaid in eastern Ulster. He took 32 mailed horsemen and some 300-foot soldiers north into Meath. Despite the small size of his force, de Courcy’s attack caught the Ulaid by surprise forcing the over-king of Ulaid, Rory MacDonleavy to flee.

About a week later, MacDunleavy returned to Downpatrick with a great host drawn from across Ulaid, however despite being vastly outnumbered, de Courcy’s forces won the day.MacDonleavy followed up this attack with an even greater force made up a coalition of Ulster’s powers that included the king of the Cenél nEógain, Máel Sechnaill Mac Lochlainn, and the chief prelates in the province.Again the Normans emerged victorious, even capturing the clergy involved included the Archbishop of Armagh, the Bishop of Down, and many of their relics.

Despite forming alliances, constant inter-warring amongst the Ulaid and against their Irish neighbours continued oblivious to the threat of the Normans.[4] De Courcy would take advantage of this instability and from his base in Downpatrick set about conquering the neighbouring districts in Ulaid.

The Battle of Down, also known as the battle of Drumderg took place on or about 14 May 1260 near Downpatrick. A Gaelic alliance led by Brian O’Neill (High-King of Ireland) and Hugh O’Connor were defeated by the Normans.

The forces of Brian O’Neill has been raiding the Norman Earldom of Ulster after 1257 in an attempt to assert their independence and form a coalition of the Irish against the Normans. O’Neill allied with Hugh McPhelim O’Connor of Connacht and together with their men went into battle against the Normans. According to the Annals of Innisfallen, the Normans had gathered an army of mostly Irish Gaelic levies to fight against the coalition, and the Normans themselves played only a small role in the fighting. Many of the Irish clans in Leinster, Ulster, Munster, Meath, and Breifne, which were under Norman rule at the time, provided the Normans with the bulk of their fighting forces, serving as mercenaries and retained bands. Thus, most of the battles between the Normans and Irish at this time would have seemed more like battles between the Irish themselves. Brian O’Neill was defeated and killed together with a number of O’Cahan chiefs.

But the people who gathered for the wedding at Ballee that day had their own tales. For many of the Ballyclander folk it was the first chance they had to get first hand news about the events that had been occurring in Belfast in recent times. The men gathered in tight circles to hear the latest news from relatives who had travelled to the wedding. Belfast was only 30 miles away but it could have been the other side of the world.

Voices were lowered as groups of men outside the Ballee church heard that only four months earlier confrontations between crowds of Catholics in Belfast degraded into stone throwing and two Methodist ministers were beaten with sticks. The next night Protestants from Sandy Row went into the Catholic areas, smashed window and set houses on fire. The unrest turned into 10 days of rioting. According to those who knew, sporadic gunfire had been heard all over Belfast in the following days.

There was also news about the health and economy of the country as a result of what had become known as the Great Hunger. News that people continued to leave Ireland to head overseas where they hoped they would discover a better life.

The close-knit families of Ballyclander and surrounding Townlands may have escaped the worst of the Great Hunger that overwhelmed Ireland during Charles and Eliza’s childhood years. Perhaps it was the isolated nature of the region or the fact they mainly grew barley, rather than potatoes, but there was no evidence from death certificates of the level of fatalities that occurred around Ireland during this tumultuous period of history. There is evidence, however, that six families in Ballyclander received famine relief in August 1847 (rosdavies.com) . Ulster counties of Cavan, Fermanagh and Monaghan lost nearly 30 percent of their inhabitants during this time. In 1847 the worst affected areas in Down including the Mournes and the fishing port of Kilkeel, only a few hours away from Ballyclander by horse and cart.

During this period known outside of Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, about 1 million people died and 2 million more left the country,causing the country’s population to fall by 20%–25%. While the Ballyclander families may not have experienced the health crisis of others, there was undoubtedly an economic impact.

All of the Conn children, Charles and his brothers and sisters, were baptised in the Ballee Non-Subscribing Presybyterian Church. The list of baptisms for that church showed that there were quite a number of babies with the surname Conn that were also baptised in the same church between 1820 and 1860, undoubtedly relatives of Charles’ family, but there is information that many of them, most of them residents of Tullinagrange, left for the United States of America, a favourite destination for many of the two million who left Ireland for better shores.

Charles’s brothers were also among those who left Ireland over time. William was married to Ann Hill in Ireland in 1864, but by 1881 he was shown in an English census as living in Oldham, Lancashire. William and his family lived in England for their rest of their lives. James was married to Ann Larmour in Ballee. Their first daughter Catherine was born in Belfast in 1874, but when she died two years later they were living in Oldham, Lancashire. James too, died in Oldham where his family was established. Like so many other Irish families, the Great Hunger may have led the two Conn brothers to leave their homeland for a better life.

Charles and Eliza welcomed their first child, Annie Eliza on February 20, 1858, just three months after their wedding and on March 7 she was baptised in the same church as her father and her uncles and aunts, the Ballee Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church. Their second child, John, was born two years later in 1860.

Charles died in 1887, but had the privilege before his death to see his daughter married. Annie Eliza Conn married James Craig on October 1, 1885 at the Carlisle Memorial Methodist Church in Belfast.

Eliza died five years later in 1893 just in time to see her first grandchild, my grandmother. Mina Craig.

Rob Douglas, Perth, Western Australia. 2021.